| layout | title | description |

|---|---|---|

default |

Beginners Track - Linux Containers |

collabnix | DockerLab | Docker - Beginners Track |

Container comprises several building blocks, the two most important being namespaces and cgroups (control groups). Both of them are Linux kernel features.

Namespaces provide logical partitions of certain kinds of system resources, such as mounting point (mnt), process ID (PID), network (net), and so on. To explain the concept of isolation, let's look at some simple examples on the pid namespace.

The following examples are all from Ubuntu 16.04.2 and util-linux 2.27.1. When we type ps axf, we will see a long list of running processes:

$ ps axf

PID TTY STAT TIME COMMAND

2 ? S 0:00 [kthreadd]

3 ? S 0:42 \_ [ksoftirqd/0]

5 ? S< 0:00 \_ [kworker/0:0H]

7 ? S 8:14 \_ [rcu_sched]

8 ? S 0:00 \_ [rcu_bh]

ps is a utility to report current processes on the system. ps axf is to list all processes in forest.

Now let's enter a new pid namespace with unshare, which is able to disassociate a process resource part-by-part to a new namespace, and check the processes again:

$ sudo unshare --fork --pid --mount-proc=/proc /bin/sh

$ ps axf

PID TTY STAT TIME COMMAND

1 pts/0 S 0:00 /bin/sh

2 pts/0 R+ 0:00 ps axf

You will find the pid of the shell process at the new namespace becoming 1, with all other processes disappearing. That is to say, you have created a pid container.

Let's switch to another session outside the namespace, and list the processes again:

$ ps axf // from another terminal

PID TTY COMMAND

...

25744 pts/0 \_ unshare --fork --pid --mount-proc=/proc

/bin/sh

25745 pts/0 \_ /bin/sh

3305 ? /sbin/rpcbind -f -w

6894 ? /usr/sbin/ntpd -p /var/run/ntpd.pid -g -u

113:116

You can still see the other processes and your shell process within the new namespace.

With the pid namespace isolation, processes in different namespaces cannot see each other. Nonetheless, if one process eats up a considerable amount of system resources, such as memory, it could cause the system to run out of memory and become unstable. In other words, an isolated process could still disrupt other processes or even crash a whole system if we don't impose resource usage restrictions on it.

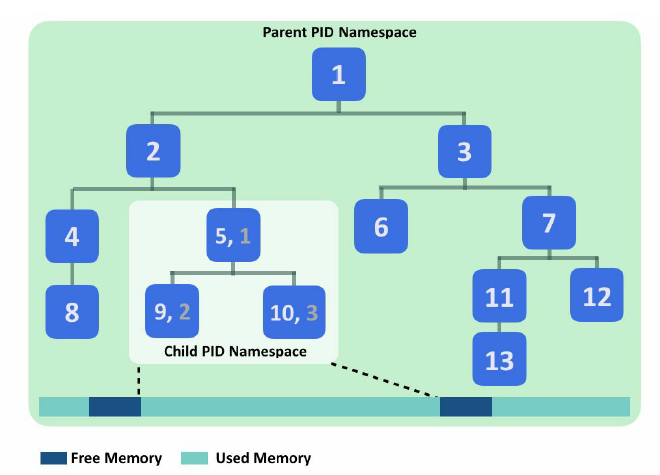

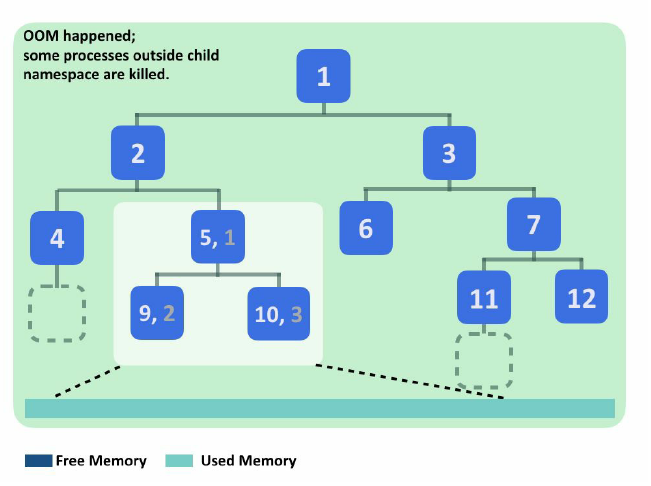

The following diagram illustrates the PID namespaces and how an out-of-memory (OOM) event can affect other processes outside a child namespace. The bubbles are the process in the system, and the numbers are their PID. Processes in the child namespace have their own PID. Initially, there is still free memory available in the system. Later, the processes in the child namespace exhaust the whole memory in the system. The kernel then starts the OOM killer to release memory, and the victims may be processes outside the child namespace:

In light of this, cgroups is utilized here to limit resource usage. Like namespaces, it can set constraint on different kinds of system resources. Let's continue from our pid namespace, stress the CPU with yes > /dev/null, and monitor it with top:

$ yes > /dev/null & top

$ PID USER PR NI VIRT RES SHR S %CPU %MEM

TIME+ COMMAND

3 root 20 0 6012 656 584 R 100.0 0.0

0:15.15 yes

1 root 20 0 4508 708 632 S 0.0 0.0

0:00.00 sh

4 root 20 0 40388 3664 3204 R 0.0 0.1

0:00.00 top

Our CPU load reaches 100% as expected. Now let's limit it with the CPU cgroup. Cgroups are organized as directories under /sys/fs/cgroup/ (switch to the host session first):

$ ls /sys/fs/cgroup

blkio cpuset memory perf_event

cpu devices net_cls pids

cpuacct freezer net_cls,net_prio systemd

cpu,cpuacct hugetlb net_prio

Each of the directories represents the resources they control. It's pretty easy to create a cgroup and control processes with it: just create a directory under the resource type with any name, and append the process IDs you'd like to control to tasks. Here we want to throttle the CPU usage of our yes process, so create a new directory under cpu and find out the PID of the yes process:

$ ps x | grep yes

11809 pts/2 R 12:37 yes

$ mkdir /sys/fs/cgroup/cpu/box && \

echo 11809 > /sys/fs/cgroup/cpu/box/tasks

We've just added yes into the newly created CPU group box, but the policy remains unset, and processes still run without restriction. Set a limit by writing the desired number into the corresponding file and check the CPU usage again:

$ echo 50000 > /sys/fs/cgroup/cpu/box/cpu.cfs_quota_us

$ PID USER PR NI VIRT RES SHR S %CPU %MEM

TIME+ COMMAND

3 root 20 0 6012 656 584 R 50.2 0.0

0:32.05 yes

1 root 20 0 4508 1700 1608 S 0.0 0.0

0:00.00 sh

4 root 20 0 40388 3664 3204 R 0.0 0.1

0:00.00 top

The CPU usage is dramatically reduced, meaning that our CPU throttle works. These two examples elucidate how Linux container isolates system resources. By putting more confinements in an application, we can definitely build a fully isolated box, including filesystem and networks, without encapsulating an operating system within it.

A basic physical application installation needs server, storage, network equipment and other physical hardware on which an OS is installed. A software stack -- an application server, a database and more -- enables the application to run. An organization must either provision resources for its maximum workload and potential outages and suffer significant waste outside those times or, if provisioned resources are set for average workload, expect traffic peaks to lead to performance issues.

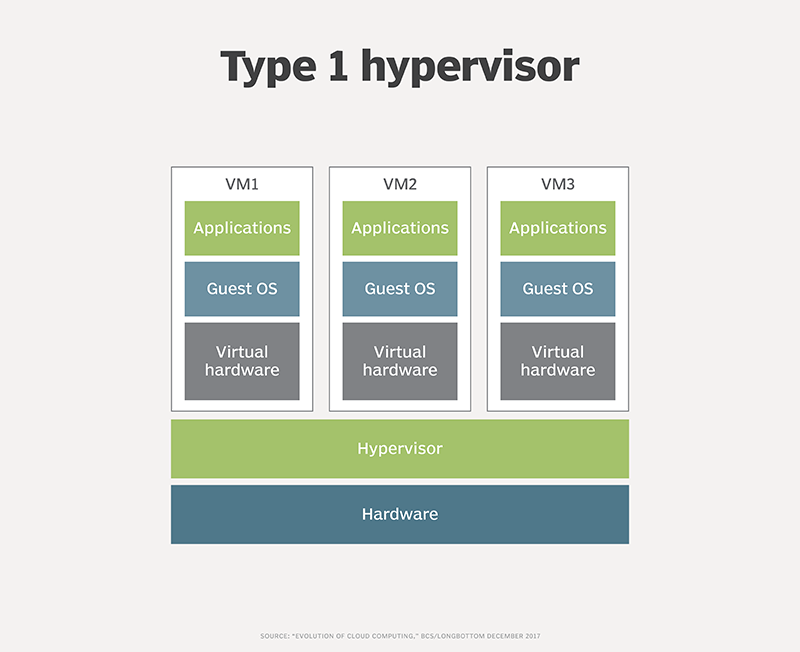

VMs get around some of these problems. A VM creates a logical system that sits atop the physical platform (see Figure 1). A Type 1 hypervisor, such as VMware ESXi or Microsoft Hyper-V, provides each VM with virtual hardware. The VM runs a guest OS, and the application software stack interprets everything below it the same as a physical stack. Virtualization utilizes resources better than physical setups, but the separate OS for each VM creates significant redundancy in base functionality.

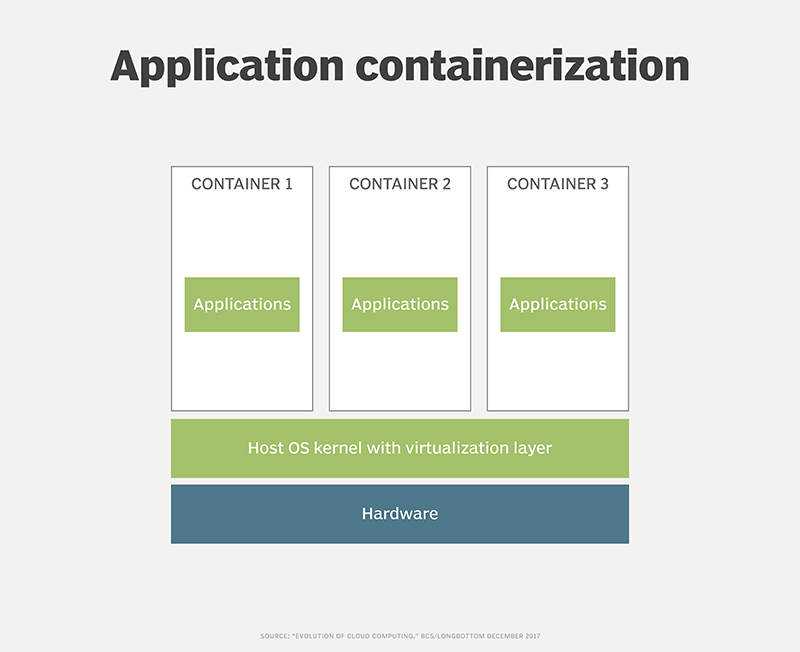

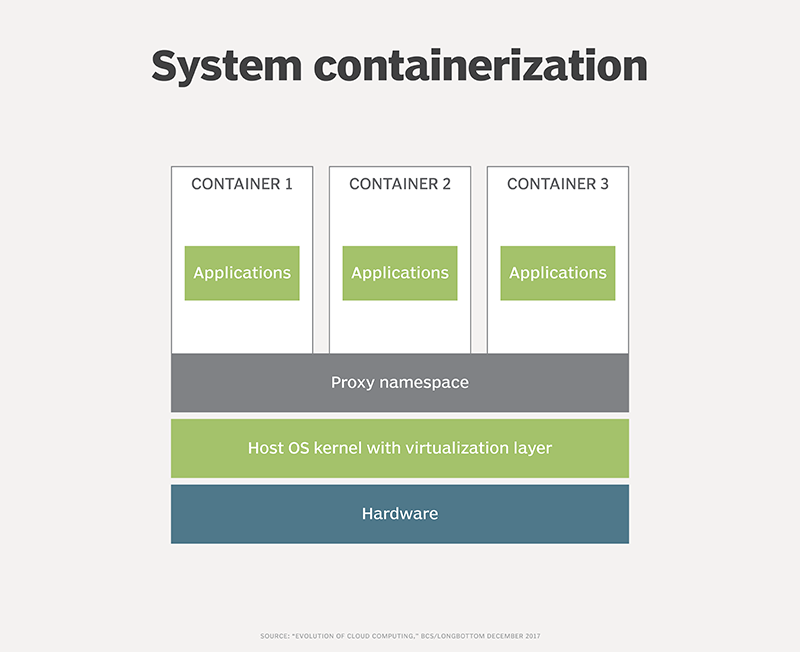

Containers provide greater flexibility than virtual and physical hardware stacks. A basic application container environment, as seen in Figure 2, runs on physical -- or virtual and physical -- hardware, a host OS and a container virtualization layer directly on the OS. Containers share the OS and its functions instead of running individual OS instances. This greatly reduces the resources required per application. Docker, Rkt (a CoreOS container runtime acquired by Red Hat), Linux Containers and Windows Server Containers operate generally in a similar manner.

OS sharing led to problems in early containers. Code that required raised privilege at the OS level opened businesses to the potential of malicious entities able to gain access to, and attack, the underlying platform to bring down all the containers in the environment. Some organizations ran containers within VMs to combat the issue, but others argued that doing so destroyed the point of containers. Modern container environments mitigate these security issues, but many organizations still host containers in VMs for security or management reasons.

The fact that all container applications must use the same underlying OS is a strength, as well as a weakness, of containerized applications. Every application container sharing a Linux OS, for example, must not only be based on Linux, but also on the same version and often patch level of that Linux distribution. That isn't always manageable in reality, as some applications have specific OS requirements.

System containerization, demonstrated in Figure 3, resolves this tangle. System containers use the shared capabilities of the underlying OS. Where the application needs a certain patch level or functional library that the underlying platform lacks, a proxy namespace captures the call from the application and redirects it to the necessary code or library held within the container itself.

System containerization is available from Virtuozzo. Microsoft also offers a similar approach to isolation via its Hyper-V containers.

Applications have evolved through physical hardware to VMs to containerized environments. In turn, containerization is ushering in microservices architecture.

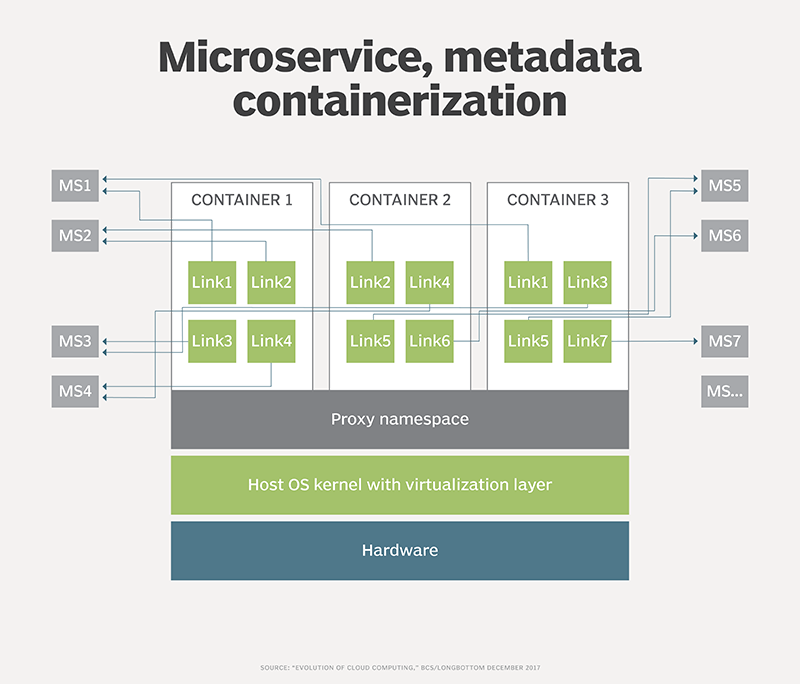

Microservices create single-function entities that offer services to a calling environment. For example, functions such as calendars, email and financial clearing systems can live in individual containers available in the cloud for any system that needs them, in contrast to a collection of disparate systems that each contain internal versions of these capabilities.

Performance benefits from hosting such functions in the cloud. Sharing the underlying physical resources elastically with other functions minimizes the likelihood of hitting resource limits.

Microservices also offer flexible, process-based methods to handle business needs in an application architecture. Rather than code that tries to guess at the business process and ends up constraining it, microservices create a composite application of dynamic functions pulled together in real time that enables a business to respond to market forces more rapidly than monolithic applications can.

As shown in Figure 4, the container doesn't carry around physical code within it, but rather a list of required functions that it pulls together as required. The container manages areas such as technical contracts and process audits.

IT professionals can soon expect to see how containers will evolve from here. Containers exist in a highly dynamic and changing world. They optimize resource utilization and provide much needed flexibility better than their predecessors, so enterprise IT organizations should prepare to use them.